I have a suggestion for you today: take a step back and look around. Look at what is going on in your town, your city, your neighborhood. Look at what is happening in your family, to your friends, at your church. What do you see? Good and bad things, no doubt, sometimes all one or the other, but more often than not, a little bit of both. What is it you want to see? If you told me, I am willing to wager you would say, to see the good win out over the bad. A true victory.

Holds The Enemy

On a ridge west of Crow Agency, Montana, there are the graves of Custer’s command, tombstones on the very spots where they fell. Once upon a time, I might have taken a greater interest in their history. But not this time. I had come to the Crow Nation for a different reason: the Centennial Crow Fair. As I stood there looking at the graves, I felt it interesting that this meeting engagement of a tribal people and an industrial civilization was in such close proximity to a contemporary display of Indian culture. Again, had I come at an earlier point in my life, I might have focused on the battlefield and thought that was the more significant part of this place. But in truth, that dichotomy of tribal versus industrial is the past and the intervening time has produced a something else. It was not the Crow’s victory at Little Big Horn; indeed, their submission to the United States had come long before the battle. Yet even though they did not engage in violent resistance, the Crow Nation had survived as a people with a distinct way of life. And what was more, paradoxically, the Crow today carry on the best parts of the country that once tried to destroy their way of life.

Sand in the Gears

But the problem is that protesting of the classic variety simply reinforces this position. With every placard and slogan, we confirm the symbolic authority of these inept politicians. It feeds the old dichotomy of rights vs. utility, one which will never be resolved, as Alasdair MacIntyre notes. It makes people decide who is the hero and who is the villain.

What My Grandfather Could Do

Living in the Truth in the Pandemic

“Living within the truth, as humanity’s revolt against an enforced position, is . . . an attempt to regain control over one’s own sense of responsibility.”

The coming summer heat teased us this past weekend and my wife and I couldn’t bear to stay inside. Personally, I am not afraid of this coronavirus — I made a conscious decision not to be afraid of it, because I realized that perfect prevention was impossible and we will all meet the virus eventually — so we went for a walk through emptied-out downtown Raleigh.

After checking out the future location of my wife’s new art studio, we sauntered a bit. Across a street corner, I saw this poster and almost immediately shook my head:

I rarely have the best sense of how to describe something at a given moment. It’s why I’ve avoided joining debate teams — my best thoughts come after marinating. I wanted to say this poster was the messianic state or trampling out the grapes of wrath or making the world safe for vaccine companies or some other sort of pithy saying. It never came.

Instead, I realized it had already been said:

“Obviously the greengrocer is indifferent to the semantic content of the slogan on exhibit; he does not put the slogan in his window from any personal desire to acquaint the public with the ideal it expresses. . . . The slogan is really a sign, and as such it contains a subliminal but very definite message. . . . “I, the greegrocer XY, live here and I know what I must do. I behave in the manner expected of me. I can be depended upon and am beyond reproach. I am obedient and therefore I have the right to be left in peace.””

The sinking feeling sets in. Yes, that’s it, isn’t it? This shopowner or restauranteur or whatever establishment he ran probably gave as little thought to the deeper significance of the slogans in his window as a greengrocer in a Communist police state.

Why, though? Does he really think that people standing six feet apart is going to stop a virus that seems to be evolved (or engineered?) to spread with enormous ease? Or has he simply accepted this as gospel because the government has proclaimed that this magical distance will thoroughly banish the miasmas which we now believe everyone carries with them in a miniature cloud?

Again, look to Havel:

“We have seen that the real meaning of the greengrocer’s slogan has nothing to do with what the text of the slogan actually says. Even so, this real meaning is quite clear and generally comprehensible because the code is so familiar: the greengrocer declares his loyalty . . . in the only way the regime is capable of hearing; that is, by accepting the prescribed ritual, by accepting appearances as reality, by accepting the given rules of the game. In doing so, however, he has himself become a player in the game, thus making it possible for the game to go on, for it to exist in the first place.”

The above poster is less about whether or not social distancing makes sense empirically than it is about the relative social position of the proprietor who hung it up. He wants to be seen as a “responsible” person, because responsible people are looked upon favorably by fellow citizens, by the press, and in culture. Also, "responsible” people don’t get harassed by the police, written up for obscure code violations, dragged through endless court proceedings, have their financial accounts audited every year, have surprise health inspections, or find themselves subject to any number of interpositions by the government. If being “responsible” is to avoid the excesses of government intrusion on one’s private life, then the corollary is that one should be responsible in the way that the government says. Hence the call for social distancing. And yet without the proprietor complying, without him on his own volition adding to the panorama of consistent, insistent messaging, the government would not be able to create the sensation of an inescapable society in which it is impossible to do otherwise than socially distance.

Of course Havel says we must be responsible. I am sure some would say that social distancing is responsible. But let us not confuse Havel’s view of responsibility with the social “responsibility” pushed in the government edicts and media-industrial complex propaganda. Responsibility ultimately springs from a moral position — it is the decision of an individual to act and to accept the consequences for it. This is as far as possible from what this poster is doing. In chiding people to be responsible, the creator of this poster actually takes no responsibility himself. He takes what a distant authority says is responsible and pushes it on someone one else. Having passed on the responsibility to be responsible, he is done; he can rest easy. For the consequences for the edicts on social distancing, mask wearing, economic lockdowns, and perhaps future mandatory vaccinations will fall on people who had no choice in the matter. When those people resist their own dehumanization by absurd protocols and social shaming, attempting to reclaim responsibility by returning to work and ordinary life, they are shamed as irresponsible. But in reality, they are the ones facing tough choices: between catching the virus at work or staying home and starving, between doing what they think is best for their own health and being as conscious as they can to not infect others. It is an fraught position, but all positions of responsibility are. What is not actual responsibility, though, is hiding behind straw men, bad data, flawed models, pet principles — and empty slogans.

This pandemic has really shown everyone’s true colors. The fact of the matter is that the United States is in a strange state; like this shop sign, there are other uncanny similarities to the post-totalitarian world described by Havel. Equally so, there are other indications that a sizeable people trust the centralized nation-state even less. My friend passed a gun store and there was a line all the way down the sidewalk, chairs six feet apart, and management handing out 4473 forms for background checks — the opposite of a socialist bread line. What happens when the unstoppable force meets the immovable object? I don’t know. But what I want to find out is, in such a clash of historic forces, where are the opportunities for living in the truth?

There’s more to write on Havel in today’s world, so stay tuned. I will update this page with links to future posts in this series.

. . . And The Strong Grow Great

The Rancher & The Sheriff

These are two Americans, just ordinary guys, without great station in the world, facing the fact that the situation they are in could get very bad. Not just for them, but for everyone in the country, should events spiral out of control. They speak like men, offering what they see is the solution, and they listen to the other, even if they are not convinced. Then they shake hands and depart, back to wait to see what comes.

From One South To Another

The last time I was in Korea, I said to myself that I had to leave and then come back. That was the only way I could improve the experience; there were too many roadblocks ahead of me from where I stood that time. So I left and went home to the U.S., where I have spent the last three years. And now, in a great paradox, in order to move ahead in my own country, with my Korean bride beside me, I have to leave the U.S. for a while in order to return.

This is beginning to feel like a recurring theme in my life, running away to return again. Yet it is the fact of this age we live in. It is a reflection of the absurdities of modern civilization and the very unsustainability of it for the average person who has not resources nor connections to smooth over or bypass the obstacles put between them and their living.

The Most Brutal Facts

While not the sole component of success, belief that you can succeed is the sine qua non of any achievement. Everything else may be ripe, but you don't think it, you won't try it, and the opportunity will pass. That is what the reluctant No voters and the die-hard Unionists could not see: that numbers don't ever give confidence. All that numbers can do, from the standpoint of agency, of autonomy, is tell you what is easy and what is hard and what is nigh on impossible. Those who voted No did not look at the numbers and vote rationally, as pundits like Alex Massie are wont to claim. They used numbers to rationalize their own uncertainties and gave up a measure of independence, both societally and personally, in the process.

The SNP Left and the New Scottish Identity

The spirit of last year's independence referendum, far from being alive and well as many claim, is dead. The open, positive, non-partisan manner in which the vast majority of Scots experienced at a personal level the debate on their country's future has disappeared. The mythologizing of the ascendency of the SNP MPs now at Westminster has turned the meaning of that experience on its head and has created, if inadvertantly, an emerging Scottish identity that is intimately associated with being on the Left, one which has the potential to monopolize national identity in terms of a single political ideology, to the exclusion of other definitions and to the danger of social and political life in an independent Scotland.

The Hyper-real and Scottish Dependence

In the UK, the year of the referendum has passed and the year of the general election has come. Another year lost to politics, some are probably wailing to themselves. Does it have to go on and on like this? There is a feeling that the Scottish independence referendum settled nothing, and nobody is happy about the outcome. Those fighting for independence are furious that they were so close but didn't achieve their long-sought dream, and the unionists are livid that the matter has been turned into a union-wide issue of political representation and power. UKIP is a specter haunting the Tory strongholds of Middle England, Plaid Cymru and the Greens join in on the edges, and Labour faces decimation thanks to its dependence on Scottish seats. The politicians are probably the most furious at this situation, for it appears that now people are actually going to take out their frustrations at the ballot box and on them, a concept that the whole "back to business as usual" tone of the Better Together referendum campaign tried to prevent. The grumbling acceptance of the imperfections of a binary choice (Labour or Tory) has been replaced by acceptance of nothing. Everything is up for grabs and for once that is directed from the bottom toward the top and not the other way around.

This fact appears as deeply partisan exchanges in opinion columns and on social media, some of it little different from what was thrown back and forth in the poorer moments of the referendum campaign. What has been lost, for certain, is the decorum with which deep and complex discussions were held, among friends and family, in pubs, everywhere. I remember that even on the day of defeat, when bitterness could have prevailed, there was still a feeling from from the passing Glasgow vox populi that the referendum campaign had raised issues that had never seen the light of day. Ordinary people who had often been disenchanted with politics all of a sudden had a choice that was beyond the scope of ordinary political dichotomies. That was the experience of most Scots, and it seems that the rest of the UK wants to have the same discussion. The difference is, the Scots had two years of debate and the Yes vote and No vote did not cleave cleanly down lines of ideology, class, party, age, or religion. Their choice was about which broad direction an entire country was to go and all the benefits and uncertainties of either way. In contrast, this year's general election, even though it is being fought on the terms of the referendum and its immediate aftermath, is a narrow, partisan event that many expect to deliver what even a deeply democratic experience as the referendum could not.

Things aren't working and they need to change -- that's the feeling across the UK. In Scotland, the contest is largely down to the Scottish National Party versus Labour. The latter is hamstrung by its collusion with its very Parliamentary enemies in the Better Together campaign and by the fact that they can no longer effectively say that unless Scotland votes Labour, there will be a Conservative government in Westminster. That trope has played out, nobody believes it anymore. The SNP, on the other hand, looks as if it could be the power broker in a hung Parliament. It would probably be willing to make a coalition with either the Tories or Labour in exchange for leverage over Scottish matters, that much is plain:

Labour paints this in the traditional terms of the SNP being "Tartan Tories," but they miss the point. The SNP has always been a big tent with one purpose: independence or anything just shy of it. All other policy -- its courting of big business, its supposedly social democratic heart -- has, is, and will be secondary. Whatever deals with the devil the SNP would have to make with the Tories (or Labour) to get what it wants is perfectly in keeping with its conception of itself. And what's worse for Labour is that many of the SNP's nearly 100,000 new members know this. The party is a means, not an end, and an institutional party like Labour can't see that.

Yet from this emerges the conventional wisdom that Scottish independence is inevitable, that by determination and seizing opportunities it can be forced to happen. This belief is strong among SNP supporters but also many of the third groups involved in the Yes campaign that continue on: National Collective, Radical Independence Campaign, Women for Independence, etc. They are trying to organize, entrench their newfound position in Scottish society, and redouble their efforts in new and more sophisticated ways. There is also an explicitly pro-independence newspaper in Scotland now, The National, which has outperformed even the venerable Scotsman and equalled the Herald in circulation. By these signs, independence seems alive and well. But this should not be confused with the actual chances for Scottish independence, in the near or somewhat distant future. Or, said differently, this flurry of political activity and engagement by an ever-more significant section of civil society should not be confused with actual efficacy in the political arena. Just because many many Scots are working hard at independence or devolution, just because the SNP is a phoenix from the ashes, and just because the Westminster establishment is threatened on all sides by the politically disaffected, does not mean that there can be a true political answer, clear and final, to Scottish independence. The very nature of modern society and politics makes that almost impossible, for that would require power. But there is no real power remaining in modern political life, not as a crystallization of vision, will, and definitive action.

This is what Jean Baudrillard, the iconoclastic French thinker, contended in much of his philosophy, but in particular his work The Divine Left. In the book, Baudrillard analyzes the Left in France in the late '70s and early '80s. While Baudrillard's portrayal of French politics and especially the French left does not translate directly to the situation in Scotland, his observations about political institutions and the people that adhere to them are still, thirty years on, unfortunately very true. Take, for example, his characterization of the French Communists:

“The Party is a shelter for all the disoccupati of politics. Anti-depressant, anti-melancholic, distributor of a hormone-injected politics, it still constitutes a haven, glimmering with the light of the social, for everyone to which history dealt a harsh blow. It manages political unemployment just as the Department of Labor manages professional unemployment.”

Again, this does not translate directly to Scotland, for which is "the Party" in Scotland now, Labour or the SNP? But it is true in a certain way. The SNP obviously is still in power in the Scottish Parliament, but that is not its purpose. The Scottish Parliament can grant itself nothing more than it already has, and so long as the SNP does not have the power to create and govern an indepedent Scotland, it is indeed in political unemployment. But the party is doing a fantastic job of dispelling this fact with a brave and jovial face. Perhaps out of necessity, it has become "anti-depressant" and "hormone-injected" in the wake of the referendum defeat. In late November, the SNP held its very own "Tour" at the Hydro in Glasgow, replete with musical acts and cheering fans with foam fingers. Was it a rock concert or sporting event? It hardly matters, for politics must now necessarily be indistinguishable from the rest of society. However much people might decry this subjection of all life to the political, this emergence of politics-as-entertainment was a natural response to all those disaffected Yes voters looking for meaning and a home in the wake of September 18. People who had six months ago said, "I don't like Alex Salmond but I'm voting Yes" have been signing up as SNP in droves. The SNP provides structure for those faced with the bewildering apolarity of a society they thought they knew but which voted No. And they are welcomed, no matter whether they are non-partisan voters coming to politics for the first time or long time devotees, perhaps of the other "Party," the newly moribund Scottish Labour. The latter once filled the role of the SNP for the disenchanted, especially in the wake of Thatcher, and it is now experiencing that the political unemployment line is just as cold and biting as the ordinary one.

This critique is not to discount what the SNP stands for or what independence supporters want in joining its ranks. But this view is necessary to make sense of the fact that that often defeat brings about a sort of cognitive dissonance about one's future chances:

“When we are denied victory, whether parousia or a parody of the revolution’s final coming, we will be able to invest in a long term policy with fanatical resignation, even more fanatical since it is destined to fail. ‘We’ll show them in five years!’”

Consider, then, that even though the SNP could make huge gains in the general election next year, the third largest political party in the UK still does not have a broad, majority appeal. It is still a minority of Scots who are interested in outright independence. In the general election, the SNP could for once find itself on the winning end of the first-past-the-post electoral system -- the Unionists remain divided, adhering to their party loyalties, whereas independence backers, even if they are not party members, will vote SNP tactically, as it's the only party to come out of the whole indyref with its image untarnished. The Yes vote will go to the SNP on the expectation of results by the Nationalists. Yet the expectation that the Nationalists could hold the balance of power in a hung parliament assumes that the main political parties own lust for power and hatred of their traditional opposition would trump fears of SNP demands on devolution and future referendums. Labour, the Tories, and the Lib Dems closed ranks once on the issue of Scotland -- they could certainly do it again.

Yet the issue of what party sends the most MPs to Westminster in May is really a distraction. However people vote, the referendum already gave the best indication of what the Scots prefer when it comes to their political options. Even though the referendum was 55% No and 45% Yes, it was only in latter weeks that it was in that range, and Yes only breached the 50% for one poll. For much of the campaign, independence often polled less than 40% -- that is, perhaps sixty percent of Scots preferred to keep things as they were rather than change them. Of course, a Yes vote did not necessarily mean a fundamental and immediate change in political power in Scotland. But it offered a chance to make something more contiguous with the small population of Scotland as opposed to the unwieldy Union. It was a chance at having Scotland governed by its own reflection. But that was not what Scots wanted.

“They do not want to be “represented.” They want to witness a representation. . . . They’ve had enough of a destiny of representation, whatever it is. They want to enjoy the spectacle of representation. . . . [T]hey prefer the spectacle of politics, whether grotesque or ridiculous, to the rational management of the social.”

However absurd Westminster and its brand of politics is, the majority of Scots still wanted it on September 18 and probably will still tolerate it today. When Cameron, Miliband, and Clegg dashed north of the border to beg and plead for Scotland to stay, many commented it was like an episode of The Thick of It. It was a hyper-real event, in Baudrillard's terms, where the simulation of an event suddenly becomes the model for what actually happens. But even if people saw through the charade, they still voted to keep it. For as much as they liked to gripe about "broken Britain," the Schadenfreude of the political classes alternating between arrogance and pandering to the masses at the drop of a hat was too good to resist. The entertainment of what passes for reality is better than taking the droll responsibility of actual reality into your own hands.

But few, if any, Scots will admit that. For almost as soon as the referendum hangover had dissipated, the cameras turned back to this impending general election. And those Scots who had the chance to deliver an opportunity for change but still voted No, are going on and on about kicking out the Tories and bringing about justice in Britain. Once again, Baudrillard has predicted this:

“This is the silent and ironic efficacy of the random masses: we’ve tested the social on them for a long time; today they’re experimenting with politics, or what remains of it, on the very title-holders of the political class. Turning against their defenders and, in all probability, against their own interests, the silent majority, nevertheless, continues leaning toward the Left and seeking some obscure goal, which is certainly not quality of life, or the satisfaction of its needs, or its ‘right to the social.’”

The infatuation with the Left, with its undercut, oversold notions of change and justice, is the only constant among the Scots that could have swung the referendum to independence. This idea of the Left has no actual bearing on how things function in the UK, as the Left as the Left has not been in power in a very long time (New Labour does not count). And yet it remains somehow a possibility in people's minds, just one election away from happening. And it can only happen in the form of the United Kingdom, or perhaps it should only happen in that form, the people adhering to some sort of unwritten commandment that defies all explanation. So these left-leaning unionist Scots ignored the admonitions of the very people who fought for them and voted No this past September: they slagged off the jolly and bombastic Robespierre of Salmond who fought the bedroom tax and kept free university tuition, and delivered Scotland from the brink safely back into the hands of Cameron/Miliband in order that they, ordinary people, may return to the comfort of a fight that they subconsciously know they'll never win. The Left shies away from being the Left in power because it does not actually want it, Baudrillard says. It can't have power in the UK, but it could have had power, real transformative power, in Scotland. But the left-sympathetic masses did not take it. And nothing could make them. You can't make someone want what they don't want.

So where does that leave us at this sort of end-of-history reckoning with Scotland's choices and future? The only practical conclusion is that, if Scotland gains its independence, it will not be through the expected channels of elections, debate, referendums, constitutional wrangling, et cetera. Nobody wants to, nor can, take control of such things. No, independence will come only because the internal impossibilities of the British state will render the Union pointless and more costly to maintain than the benefits reaped from it. The owners of the UK mansion will not be evicted by a mob of angry peasants; no, the grand old house will simply be foreclosed on because no one's living there any more. Make no mistake, the Scottish independence movement, the democratic awakening of the referendum campaign, and the role of the SNP in that long process will have made all of it possible in the end -- they raised issues that no one else could have, issues that are here to stay, across the UK. But the politicians, those invested with real authority, will be mere bystanders or accessories to the act. The dysfunction of the whole system prevents any of them from being the prime mover, the arbiter of the break-up of Britain or the keeper of its bonds, no matter how much electoral support they have.

When Scotland's independence comes, then, the question will still be, as it was in the indyref campaign, "What sort of country do we want to live in?" But if there is to be an answer, it must come from a realization that much of what the Yes campaign fought for, a better country, a socially just country, whatever you want to call it, was and will be impossible. How can Scots expect to deliver sweeping societal change if politicians themselves can't even deliver what they were elected to do? How can there be a well-funded welfare state, an equalitarian and inclusive society, a progressive tax system that both supports the economy and funds the state, et cetera, if the very vehicle for those goals -- independence -- is beyond the reach of even the most concerted political efforts? We can support parties like the SNP or the Scottish Greens, yes, but is the paradigm in which they must necessarily operate really what Scots want in a new country? Independence is inextricably linked with indistinct iterations of the Left, of social democracy which is, in broad form, little different from what mainstream UK parties preach. Should that same paradigm be repeated because Scots think that changing the flag outside Holyrood will make their own ideological preferences will finally work? To find an answer to all this, Scots must begin to examine why the very system of modern politics is as it is, why it functions this way, a question which then demands a reconsideration of the modern mind which, intentionally or not, built the system.

For Scotland to be the country Scots want it to be, there must be a revolution of thought to accompany any political revolution involving independence. Anything less is to keep running around and around in this interminable cul-de-sac, the hyper-real feedback loop that Baudrillard shows we're stuck in and which keeps people and nations thwarted. Revolution is a strong word, though, and one of of thought sounds particularly extreme, indeed, impossible, because our Enlightenment determinism has told us this is the right path and we should have already been there by now. That must be overturned. And I find such an act possible, though not yet plausible, for Scotland, as a small country but also as Scotland. After all, Scotland shaped the Enlightenment in ways far beyond its population size or economic power. But there's no point in dwelling on the past -- the Enlightenment and its heirs are dead and gone. They built the system we face now, a paradigm working itself out to its logical conclusion. That paradigm cannot go on and, if we're free to see that, we shouldn't let it. That is the quality of the moral choice we must make, to make independence worth it. To make being Scotland as Scotland worth it. How? Let Scotland do what it does best and reinvent things as we know it.

What Is A Scotland For?

I knew I would write a post describing the significance of the Scottish independence referendum, but it is a very different one from what I expected to be writing a few weeks ago. For then I was headed to Scotland, where the Yes campaign for independence was coming from behind with great momentum. But now you know how it turned out.

There were many mixed emotions the morning after, undoubtedly fueled by elated premature celebratory drinking and a late night at bars watching the poll returns, followed by a while on George Square while the young Tartan Army types went ballistic with their football chants and mosh pit. I look back at my notebook at what already seems like years ago and am fascinated by the black mood that the announcement produced. Yet as the rest of September 19 rolled along, as the future shape of things was already becoming apparent, and I exchanged views with Scots on the matter, many of the following thoughts began to take shape. Now, at home again, I can give them the perspective they deserve, though perhaps a little divorced from the rush and vigor of the time and place that was Scotland on its decision day.

The Scots have, to appropriate the words of the writer Allen Tate, "a concrete and very unsatisfactory history." This is their curse and strength as a people. They know who they are, they know where they come from and how they got to where they are. They know their shortcomings and their strengths, and they know what they want and what they must do but that the ultimate power in attaining that is not theirs. This makes them a complex but noble people. For they have looked at themselves and can say, "Warts and all, this is who we are." That is a refreshing trait compared to their southern neighbors, who exhibit the baffled, reflexive confusion, followed by outrage and revenge, that characterizes almost every dominant section within a country or union. The Scots are painfully self-aware; the electors of David Cameron and Nigel Farage are aware only of others.

So now the Scots have a new paradigm in their unsatisfactory history. For more than half of their country voted to remain subservient to London. For all the blaring of "Scotland the Brave" and thumping the chest shouting "Whae's like us?" when the chips were down, Scots voted not to be Scotland but to be North Britain. They basically said, "We're proud to be Scottish, but not if it involves any pain or inconvenience."

Can you say that's Scotland? If we're using democracy as a yardstick, which we moderns are wont to do, then yes. 55% of Scots said so. And I think they expected to say to the other 45% who voted Yes, "All right, you lost. Time to roll up your saltires, go home, and get back to business as usual."

Maybe the No voters didn't want to define Scotland in such a way; maybe they resented being forced to make the choice. But they made it all the same and there are consequences for that, like every decision. They've said, "We were free to go, but we're not sure who 'we' are."

But the Yes voters were sure. They put their vote where their heart was. And they've been hurt in the heart by the result, and have responded predictably. Right now they are out joining the SNP, the Scottish Greens and Scottish Socialist Party. They are organizing rallies, gathering supplies for food banks, and thinking about the future. They are planning a new, expanded vision for their groups and platforms like Common Weal, National Collective, Radical Independence Campaign, Wings Over Scotland, or Bella Caledonia. They are looking to create new, independent media sources to present a more balanced (more Scottish?) view on current events to the Scottish public. They refuse give up and press on, still in full-on campaign mode.

Who then is taking the more active role in defining Scotland? Those who voted once and made sure, through their own loyalty, naivete, fear, or complacency the tentacles of the British state remained firmly suctioned to every part of Scottish society? That majority? Or is it the minority, who are out trying to make happen what is not within their control? If it is the former, then we have the case that there is no more Scotland. The modern world has triumphed, where the relationship that truly matters is the state and the atomized individual, where the state says, "I love you more than anything in the world, but if you ever try to leave me, I'll destroy you and everything you care for."

If it is the latter, though, then there is still a Scotland, but in a new way. It is a Scotland that is not defined by the historical borders of the country. It is a Scotland where fewer people than most believe that Scots should do things for themselves, in their own way. The Yes vote was 45% but only three out of thirty-two councils went for Yes. The Yes voters are scattered geographically across the land -- they are not concentrated in one region of Scotland, where they can separate themselves from the No-voting rest of the country if they chose. This is a great disadvantage, on the face of it, but perhaps in the long run, it is a blessing. For it keeps the angry and disenchanted from breaking away from those who see differently from them. It prevents there from being, in a geopolitical sense, two Scotlands. The case of North Korea and South Korea is an example of this: two states, where each has embraced an ideology that they believe is best for the Korean people. What they hold dearest divides them.

But there are two Scotlands at the moment. Those for whom the campaign still lives on, and those who are returning to their lives, perhaps uncaring about the result, perhaps slipping back into their old cynicism about politics after the Cameron-Miliband-Clegg "Vow" turned out to be a complete fabrication. What remains to be seen is whether there will be reconciliation or triumphalism. If there is reconciliation between Yes and No, then some sort of new iteration of Scottish identity may emerge. If there is triumphalism, then one of the two narratives will become the dominant one. And it is entirely possible, despite its minority position, that the Yes campaign will write the history. It has reason to, because it must convince future generations (even if can't convince No voters now) that it was right. But even if they are successful in that effort, what fact lurks is that the Yes campaign had to protect an idea of Scotland against the will of most Scots. It would thus be a minority view foisted on the rest by the will of the more committed.

What then is a Scotland for? Is it for what the people want, even if they don't want it as its own distinct thing, a separate and independent nation? Or is it for itself, built upon history and traditions of self-rule and those who would protect and re-articulate those traditions? How can we call for democracy on the one hand and appeal to the idea of a nation on the other when they are not used in concert? Is the fact that only a minority of Scots wanted independence an indication that, for most, countries are now merely images bought, sold, and displayed by the rulers? Is the rage of the Yes minority an indication that the nation does not actually function behind the scenes like it is purported to by every face the state presents to the public?

The fact that we must ask these questions demonstrates that we have come to a strange time in the idea of a nation. Not the nation-state, not the Westphalian creation that puts an all-encompassing centralization and homogenization at its core. Rather, it is the nation as a collection of people who have common experience; who have governed and been governed by each other; who influenced and were influenced by each other; who make something which is complex and nuanced, but not relative. It has a word -- in this case, Scotland or Scots or Scottish -- so it is real, it is a thing, distinct from others. Going into the Scottish independence referendum, I thought the moment would demonstrate the fact that people have instincts and loyalties to something older and more immediate than the abstractions of the modern state. But I can see now that I was wrong. This was no rebellion of the anti-modern. The relationship of the state, which merely uses the idea of nation or people or identity as a image to cloak itself, to the individuals it rules is the dominant one in our world. It holds the allegiance, or the fear, of most people, and makes the idea of democracy obsolete because of the codependency it fosters.

So on the one hand the state has trumped any of our attempts at recalling shared experience, memory, and community as a basis for creating (or restoring) polities that better serve the people who live in them. Yet on the other hand it is plain that large political units in the developed world are increasingly unsustainable. They centralize not only political power but also economic power and suck dry the hinterlands and the periphery. What cannot be sustained will not be; empires and mighty unions eventually crumble or disintegrate. So Scotland will have its chance again at independence, at self-rule. When it comes, Scotland may want it, or perhaps not. Whatever the case, Scotland will have to contend with its concrete and unsatisfactory history. It will have to decide what it is, why it did what it did, make peace with that, and move ahead. It will have to reconsider what Scotland is, and it will do so, I am sure. Yet the country cannot ever escape the fact that, given the clear chance after 300 years, it voted against being itself on its own terms. The Bannockburn glory, the "bought and sold for English gold" myth of Burns' lament, it all must be reconsidered in that light.

Scotland will one day be a new nation. But it will not be the same nation, just as it is not now. That is refreshing for what it can achieve and how it will make itself in its own vision. And yet it is also sad for what it leaves behind as a consequence of its own decisions, imperfect as they may be.

“I have said: ‘My native land should be to me

As a root to a tree. If a man’s labour fills no want there

His deeds are doomed and his music mute.

This Scotland is not Scotland.’

Like my comrade Mayakovsky

’I want my native country to understand me.

And if it doesn’t, I will bear this too;

I will pass sideways over my country

Like a sidelong rain passes.’

This Scotland is not Scotland

But an outsize football pitch

Filled with nothing

But an insensate animal itch.”

Reap The Whirlwind

When I wrote before of the Scottish independence movement as it headed toward the referendum, there were signs of positivity on the horizon, though a long way to go. But all that has changed in the last few weeks, and the global significance of this event is becoming real.

Time ran an article about the possible impending 'exit' of Scotland from the UK should the independence referendum return a 'Yes' vote. News outlets and blogs outside the UK are beginning to play catch-up and talk about how Alastair Darling, the leader of Better Together (the 'No' campaign), practically melted down during his second debate with First Minister Alex Salmond, even conceding to Salmond the one point -- that an independent Scotland could continue to use the pound sterling -- that he had resisted and ridiculed for months on end. Palpable panic has been setting in over the past week in the UK establishment. David Cameron continues pleading with Scots to vote No; Better Together has put out a series of advertisements that range from sexist to asinine; and even Nigel Farage, head of the UK Independence Party, disgruntled Middle England's knight errant against the EU, has said he'll come to Scotland in order to inject positivity into the 'No' campaign. And all the while, as the important people with the important titles beg and warn and offer veiled threats, the number of Yes voters ticks upwards. I have seen Tweet after Tweet about people converting to a Yes vote after a long period of casual inclination toward No and equally as many about passionate Yes voters making converts to their side. People are out there, talking and making decisions for themselves, and that has the establishment terrified. The rulers have been used to sowing wind for centuries, and now they are about to reap the whirlwind.

Where else in the world is having a democratic moment like Scotland? Nowhere. And has there been anything comparable in the last few decades? Hardly. Some might point to the Arab Spring or the Occupy movement as similar instances, but those are instances of protest. They gathered steam quickly, raged against the status quo, and then faded quickly when the establishment decided it had had enough. But the democratic spirit of this independence referendum does not come from mere dissatisfaction taking to the streets. Rather, it is a culmination of long political involvement, competition, and eventual success by a long-established independence movement, one that has taken both party and non-party form over nearly a century. In particular, the very willingness of the Scottish National Party to persevere in political contest, despite the many setbacks of contending with a very difficult system of political representation in the UK, has legitimized independence not as some sort of temporary emotional outburst, as the No campaign is wont to characterize it, but as a natural extension of politics as usual. Discounting the divisive figure of Alex Salmond, many of the politicians involved in the Yes campaign are not just running the devolved Scottish Government in Edinburgh but also hold seats in local government as well. They didn't get there by appointment or nepotism -- they got there because they were elected. There are enough people out there to want them in charge and now they are responsibly delivering what they said they would.

Then perhaps it should be no surprise to those of us looking from outside the UK, that the independence referendum has awakened, at least on the side of Yes, a sense of positivity and opportunity. For the Yes movement is led not simply a bunch of cranks spouting narrowly nationalist vitriol, but by competent leaders in politics, the arts, academia, media, and business. Yet while these leaders frame much of the discussion, they do not offer absolute answers. Many #indyref campaigners have, seemingly of their own accord, been willing to put foremost the uncertainty of independence and address it without fear. Indeed, they almost seem to relish in recognizing it, for it compels answers to be given. But there is no line to toe. Watch the film Scotland Yet and you will see how open the dialogue is and how everyone seems to know that independence is just the start -- all their heterogeneous ideas may make Scots vote Yes, but only because it is a Yes vote that makes those ideas a practical reality.

And those ideas will have to contend. Without a doubt there will be a tension within the politics of an early independent Scotland between the centralizers and the localists. There are those on the Scottish left who, though wishing to leave the centralized Westminster system, want a redistributive state for Scotland. Their proposals for what that would look like are as multiform as the groups proposing it, from Radical Independence Campaign to Commonweal to the Scottish Socialist Party, even to Labour and SNP supporters who want a Scottish state based on a Scandinavian model. This would require a great amount of power set in Edinburgh thanks to the taxation and administration necessary to a welfare state. But a great many Yes voters, on the left as well as of other political orientation, are more interested in communities. The writer Andy Wightman, concerned with land issues, has given the following explanation for his qualified Yes vote:

“I want a Scotland with radically greater democratic control of land, economic affairs and politics. But I have no great faith in the state to deliver this. The nation-state is a relatively modern invention and, as I highlighted at the outset, it is increasingly irrelevant to the challenges we face in communities and around the world. Indeed, it could be argued that, given the ease with which it can be captured, it is actively hostile to genuine democracy.

And that is why the choice of yes or no doesn’t adequately addresses the great challenges of our time – peace, environmental degradation, human rights and social justice. The era of the nation state is, in my view over. It is a redundant idea. But it is not going to disappear in a hurry and thus I am interested in any opportunity that provides an opportunity to completely rethinking governance.”

The centralizers may find that their vision for a quasi- (or overtly) socialist Scotland stymied, be it in the creation of the written constitution or in the politics of an early independent Scotland. This democratic moment may take things in a more confederal direction. Or the country may, as SNP critics contend, end up friendly to business and industrial interests and find itself an independent but comfortable part of the capitalist Anglosphere. Nobody really knows. These are the matters that will divide Yes voters in the future. And I'm sure that many know that. But it is their future, and there is only one way to get there. And so they embrace those different from them, in the classically Jeffersonian model of the people: the many versus the few.

For what politicians rarely understand about those they ostensibly serve is that it is not pure emotion or rationality that drives the decisions of ordinary people. You can't always scare them with the fear of the unknown, especially when they have a pretty good idea that the known isn't very rosy. And you can't throw an endless barrage of statistics and reports and experts at them, because who leads their life based on numbers and probability? Ordinary people operate off of something far deeper, off of intuition or tacit knowledge. They gather the bits and pieces of their experiences, of their relationships and conversations, and, once that has all composted for a bit, a decision emerges. And, once again, this is what the politicians and the No camp fail to see. For if we lived in a perfect world, there would be no need for decision, even to choose No and change nothing. Decision emerges from a recognition that time has outrun our patient endurance of the imperfections we know. We choose one or the other, but there is no not choosing. And if a person sees an unknown but one with potential, one in which they can play a greater role, versus the same old thing that they've always known, requiring that same old exhausting, patient endurance until the end of one's days, then it makes complete sense why people will join with others in an open and adventurous choice.

At a personal level, I am extremely grateful these past few weeks and months for what is happening in Scotland. The idea of Scottish independence has been something that has long appealed to me, even though for a long time I didn't really know why. I can remember being in my flat during my brief time living in Edinburgh, trying to start arguments with my roommates about independence and nationalism, standing up for this thing that I knew so little about but felt such an affinity for. I remember being back in America the next year, sitting alone in my apartment, listening to the Scottish Parliament elections on the BBC and cheering on the SNP as they took twenty seats at Holyrood and formed a minority government. It mattered to me, for some reason, even though it was not my country, not my fight, and I could contribute almost nothing to it. But since the referendum date was set in stone and the rhetoric began to build, I began to realize perhaps why I had gravitated toward this implausible thing. And now, as the groundswell of Yes support becomes greater by the day, I can see it for a fact: that in this sordid age of power and profit, of ideology and repression, of instability and transformation, there is still the possibility of people taking matters into their own hands and working for something better. Not just on a whim, not as a reaction, but because people take up a movement built by many who came before but did not live to see its fruition.

What will come of Scotland, who knows. But it is worth watching, and closely. For in the particular lies a bit of the universal, of the things that are true for all of us wherever we are. Watch carefully for Scotland yet, whatever yet may be.

P.S. My fortunes have changed and I've been blessed with the opportunity to go to Glasgow for the week of the independence referendum. A long-hoped for dream come true. I will report back with everything I saw and felt in due course.

The Economy and the 9/11 Kids

A regular customer of mine came into the store where I work my dead-end-but-rent-paying job and said the most interesting thing: “You know, my generation is not used to doing without – if we want something, we buy it. But your generation is much, much more frugal than we are. Y'all have got to figure out how to make money once we've gone.”

Art in the Age of Empire

What then remains within our own power? We have our opinions, reactions, and attitudes, as Epictetus notes, but I would say we also have art. We all have the capacity for art in one form or another. And by this I mean real art, art that is not subject to utility, obsolescence, or official approval. It is done for its own sake, and makes its own meaning.

Walking Ground

I walked ground with my father, in rain and heat, in Pennsylvania last week. The ground could be called many things, most probably “hallowed” by those who care to bandy about such terms. To us, it was more personal than that, more personal than some sacralized description worn out by repetition. It was about our family, and its place in a bloody, muddy, confusing past.

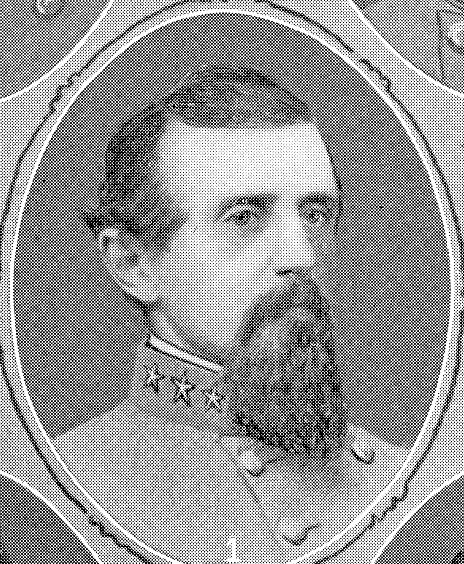

Those moments we walked ground were 150 years to the day that my great-great-great grandfather led his regiment in an attack that would unfold into the Battle of Gettysburg. We are fortunate that we have a clear picture of what he went through that first day: he wrote memoirs in his later years and there is an excellent work on his regiment's experience of the war. To study him, the man, and his path through the Civil War is to gain a complex picture of a sliver of American history. The Colonel was no firebrand. He came from Moravian stock, pacifist Germans who believed in pious, communal living. His father broke from the vocation given to him by the town fathers and started a successful mercantile store, and even sent his son on a business trip to New York City the year before the War. The family tone, therefore, sounds like the classic mid-nineteenth century Whig: lawful commerce and profit as the bedrock of society, and may nothing ever disturb it. Yet when war broke out, and North Carolina reluctantly went to fight the Union rather than supply troops to invade its fellow states, he joined the volunteers. Why? He was no secessionist in principle ---- he declared that he felt the people's rights were secure under the Constitution. Yet he also said his duty lay with his state.

The nuances of the Colonel's motives are lost to time. But it is clear that this man does not fit neatly into the preconceived (and ever-narrowing) categories that we are told today define men's motivations, and especially those of Southerners, in fighting the Civil War. There is no doubt that when men step onto a battlefield, they are motivated by a sense of getting home or never letting down their fellow soldiers ---- that is the impetus for all competent soldiers in combat. But that does not explain why men volunteer to fight in the first place. It does not explain why my ancestor, nor poor farmers, blacksmiths, and clerks -- many from parts of North Carolina with small farms, bad roads, and few slaves, all of whom had everything to lose and nothing to gain -- would go off to fight for a principle as abstract as the institution of slavery, the narrative that is fed to us. And if their experiences individually and as a unit, as a living, breathing cohesion of men, are that complex, then how much more complicated is the war itself, not to mention its roots?

But only the simple version of the battle, and the war, exists in the modern mind. The park rangers I listened to spoke with great authority about the battle in what were actually only the most general terms of the action. Unwittingly or not, they helped create the image of the battle in the visitor's mind that resembles the battlefield map ---- units in neat, mass ranks, filled with generic soldiers, led by a commander whose name becomes synonymous with either brilliance or ineptitude. Units charge or retreat, commanders lead or die, and the battle progresses to a new phase, and now step right this way, ladies and gentlemen, for our next stop on the tour.

The physicality of the Gettysburg battlefield makes this even more acute. Everywhere are granite monuments and brass placards, denoting the left flank of such-and-such regiment and the death of the heroic John Reynolds. They are convenient markers for the placement of units, but serve to reflect the space back upon the visitor. Tourists take a picture of the monument, then hand the camera to a bystander and have their picture taken next to it. And then they move on to the next one. They found the spot where this famous unit made its stand, recognized it, found it interesting, and now can move on. But did they look at or walk the surrounding ground? Did they imagine what it would have looked like without the memorials, paved roads, and minivans? And how did that physical space compare to the recollections of those who actually fought? I know that the Colonel's regiment turned the flank of a New York regiment. But what did that look like? And did they achieve surprise because they made their wide, flanking maneuver in high, thick grass? Or is it as another source states, that his regiment was hiding and waiting in the grass for the New Yorkers to arrive, and not advancing? My father and I sat for a long time on the battlefield trying to piece all this together. But first and foremost in our minds was the thought that, whatever the movements might have been and how they might appear to us on the ground today, they were for the sake of killing. Americans killing Americans. That was the purpose of it all.

But it is hard, so hard, to conceive of that. You cannot do it without information, and lots of it, in all its confusing, often contradictory forms. And to simplify that information is to annihilate any relation of that very real past to the present in which we live and which we know is complicated. We lose imagination and thus we lose realization.

Persisting, then, through all the approved descriptions and graven images and stone idols of the Gettysburg park, is the celebration of The Good War. The blood was a little less red, the cries for water or mothers from the wounded a little less shrill. It can be painless for us as a nation because it is a painted as a holy cause ---- the Gettysburg Address is Lincoln's Sermon on the Mount and his exclusive rendering of the definition of the conflict's meaning is his Beatitudes. As a people we are absorbed by the deceptive grandeur, and we lose sight of that age's complexity and the true human scale of what transpired, the waste, the death, the tragedy for the whole country.

And the conflict will forever continue to be justified: for the progressives, it was the seed of the civil rights movement, despite the facts; for the right-wingers, it was the chance for industrial capitalism to rule the whole country at its whim. Southern resistance to despotism is discounted, and Northern resistance to the excesses of its own government is not considered relevant. They are all side shows to the story of the Good War.

Most visitors at Gettysburg probably believed with little questioning most of the tenets of that story. Yet something still brought them there. Whether it was the scraggly, lanky man in dirty Carhartts and a ratty Ole Miss shirt, or a barrel-chested, pasty-skinned Midwesterner in his labor union hat, the common folk were there. They were there because someone that belonged to their family, the commoners who do the dying in our wars, had been at Gettysburg. Maybe they celebrated because they believed their ancestor had fought the good fight and won. Maybe they were overcome with melancholy for what was dared and failed, as my father and I were. In any case, we were all there, together in honor, but still divided, or deluded, by what the actions of those men meant.

On the third day, my father and I walked in a grouping of people from Seminary Ridge to Cemetery Ridge, following the path that Davis' brigade had taken in the final Southern assault. Walking that ground, you descend into a depression, unable to see your opponent. Then you rise up to one and then a second crest, when the objective finally comes into view. Only then they were silhouetted by their position on the crest, making perfect targets. My great-great-great grandfather's regiment has the horrible honor of having the most men fall farthest to the front of the Confederate line. They came within eight or nine yards of the Union troops behind the rock wall, but did not cross it.

When the commemorative Pickett's Charge march was over, our overzealous park ranger riled up the members of our group and led them in a mock charge over the rock wall. I did not go. Those men did not make it and I would not dazzle myself with any wishful imagining. We are not here to project our fantasies onto the past. If we do, those hopes will remain only fantasies. What remains to us is to understand what went awry, what led Americans to slaughter Americans for four long years, and correct our understanding. If our nation has become what we sense, what we know is not itself, then it is up to us to break down the myths that perpetuate that invidious redefinition. It is not up to us to change the past ---- it is our duty to act in its light now, without its error.