I had been back in the South less than 24 hours and already I knew by signs such as these that I was home. Not simply because what was common was familiar, but also because what was eccentric was accepted.

What My Grandfather Could Do

From One South To Another

The last time I was in Korea, I said to myself that I had to leave and then come back. That was the only way I could improve the experience; there were too many roadblocks ahead of me from where I stood that time. So I left and went home to the U.S., where I have spent the last three years. And now, in a great paradox, in order to move ahead in my own country, with my Korean bride beside me, I have to leave the U.S. for a while in order to return.

This is beginning to feel like a recurring theme in my life, running away to return again. Yet it is the fact of this age we live in. It is a reflection of the absurdities of modern civilization and the very unsustainability of it for the average person who has not resources nor connections to smooth over or bypass the obstacles put between them and their living.

Walking Ground

I walked ground with my father, in rain and heat, in Pennsylvania last week. The ground could be called many things, most probably “hallowed” by those who care to bandy about such terms. To us, it was more personal than that, more personal than some sacralized description worn out by repetition. It was about our family, and its place in a bloody, muddy, confusing past.

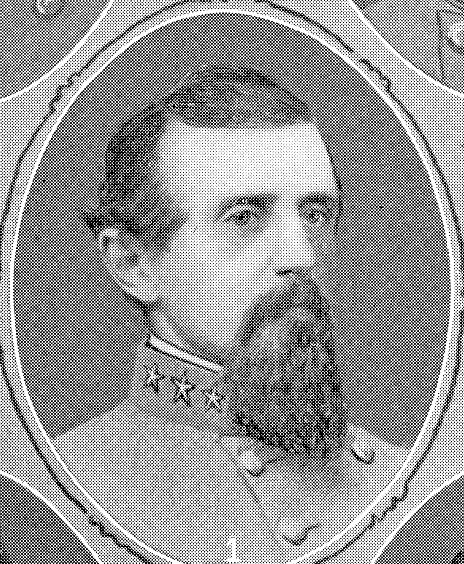

Those moments we walked ground were 150 years to the day that my great-great-great grandfather led his regiment in an attack that would unfold into the Battle of Gettysburg. We are fortunate that we have a clear picture of what he went through that first day: he wrote memoirs in his later years and there is an excellent work on his regiment's experience of the war. To study him, the man, and his path through the Civil War is to gain a complex picture of a sliver of American history. The Colonel was no firebrand. He came from Moravian stock, pacifist Germans who believed in pious, communal living. His father broke from the vocation given to him by the town fathers and started a successful mercantile store, and even sent his son on a business trip to New York City the year before the War. The family tone, therefore, sounds like the classic mid-nineteenth century Whig: lawful commerce and profit as the bedrock of society, and may nothing ever disturb it. Yet when war broke out, and North Carolina reluctantly went to fight the Union rather than supply troops to invade its fellow states, he joined the volunteers. Why? He was no secessionist in principle ---- he declared that he felt the people's rights were secure under the Constitution. Yet he also said his duty lay with his state.

The nuances of the Colonel's motives are lost to time. But it is clear that this man does not fit neatly into the preconceived (and ever-narrowing) categories that we are told today define men's motivations, and especially those of Southerners, in fighting the Civil War. There is no doubt that when men step onto a battlefield, they are motivated by a sense of getting home or never letting down their fellow soldiers ---- that is the impetus for all competent soldiers in combat. But that does not explain why men volunteer to fight in the first place. It does not explain why my ancestor, nor poor farmers, blacksmiths, and clerks -- many from parts of North Carolina with small farms, bad roads, and few slaves, all of whom had everything to lose and nothing to gain -- would go off to fight for a principle as abstract as the institution of slavery, the narrative that is fed to us. And if their experiences individually and as a unit, as a living, breathing cohesion of men, are that complex, then how much more complicated is the war itself, not to mention its roots?

But only the simple version of the battle, and the war, exists in the modern mind. The park rangers I listened to spoke with great authority about the battle in what were actually only the most general terms of the action. Unwittingly or not, they helped create the image of the battle in the visitor's mind that resembles the battlefield map ---- units in neat, mass ranks, filled with generic soldiers, led by a commander whose name becomes synonymous with either brilliance or ineptitude. Units charge or retreat, commanders lead or die, and the battle progresses to a new phase, and now step right this way, ladies and gentlemen, for our next stop on the tour.

The physicality of the Gettysburg battlefield makes this even more acute. Everywhere are granite monuments and brass placards, denoting the left flank of such-and-such regiment and the death of the heroic John Reynolds. They are convenient markers for the placement of units, but serve to reflect the space back upon the visitor. Tourists take a picture of the monument, then hand the camera to a bystander and have their picture taken next to it. And then they move on to the next one. They found the spot where this famous unit made its stand, recognized it, found it interesting, and now can move on. But did they look at or walk the surrounding ground? Did they imagine what it would have looked like without the memorials, paved roads, and minivans? And how did that physical space compare to the recollections of those who actually fought? I know that the Colonel's regiment turned the flank of a New York regiment. But what did that look like? And did they achieve surprise because they made their wide, flanking maneuver in high, thick grass? Or is it as another source states, that his regiment was hiding and waiting in the grass for the New Yorkers to arrive, and not advancing? My father and I sat for a long time on the battlefield trying to piece all this together. But first and foremost in our minds was the thought that, whatever the movements might have been and how they might appear to us on the ground today, they were for the sake of killing. Americans killing Americans. That was the purpose of it all.

But it is hard, so hard, to conceive of that. You cannot do it without information, and lots of it, in all its confusing, often contradictory forms. And to simplify that information is to annihilate any relation of that very real past to the present in which we live and which we know is complicated. We lose imagination and thus we lose realization.

Persisting, then, through all the approved descriptions and graven images and stone idols of the Gettysburg park, is the celebration of The Good War. The blood was a little less red, the cries for water or mothers from the wounded a little less shrill. It can be painless for us as a nation because it is a painted as a holy cause ---- the Gettysburg Address is Lincoln's Sermon on the Mount and his exclusive rendering of the definition of the conflict's meaning is his Beatitudes. As a people we are absorbed by the deceptive grandeur, and we lose sight of that age's complexity and the true human scale of what transpired, the waste, the death, the tragedy for the whole country.

And the conflict will forever continue to be justified: for the progressives, it was the seed of the civil rights movement, despite the facts; for the right-wingers, it was the chance for industrial capitalism to rule the whole country at its whim. Southern resistance to despotism is discounted, and Northern resistance to the excesses of its own government is not considered relevant. They are all side shows to the story of the Good War.

Most visitors at Gettysburg probably believed with little questioning most of the tenets of that story. Yet something still brought them there. Whether it was the scraggly, lanky man in dirty Carhartts and a ratty Ole Miss shirt, or a barrel-chested, pasty-skinned Midwesterner in his labor union hat, the common folk were there. They were there because someone that belonged to their family, the commoners who do the dying in our wars, had been at Gettysburg. Maybe they celebrated because they believed their ancestor had fought the good fight and won. Maybe they were overcome with melancholy for what was dared and failed, as my father and I were. In any case, we were all there, together in honor, but still divided, or deluded, by what the actions of those men meant.

On the third day, my father and I walked in a grouping of people from Seminary Ridge to Cemetery Ridge, following the path that Davis' brigade had taken in the final Southern assault. Walking that ground, you descend into a depression, unable to see your opponent. Then you rise up to one and then a second crest, when the objective finally comes into view. Only then they were silhouetted by their position on the crest, making perfect targets. My great-great-great grandfather's regiment has the horrible honor of having the most men fall farthest to the front of the Confederate line. They came within eight or nine yards of the Union troops behind the rock wall, but did not cross it.

When the commemorative Pickett's Charge march was over, our overzealous park ranger riled up the members of our group and led them in a mock charge over the rock wall. I did not go. Those men did not make it and I would not dazzle myself with any wishful imagining. We are not here to project our fantasies onto the past. If we do, those hopes will remain only fantasies. What remains to us is to understand what went awry, what led Americans to slaughter Americans for four long years, and correct our understanding. If our nation has become what we sense, what we know is not itself, then it is up to us to break down the myths that perpetuate that invidious redefinition. It is not up to us to change the past ---- it is our duty to act in its light now, without its error.