The Scots have, to appropriate the words of the writer Allen Tate, "a concrete and very unsatisfactory history." This is their curse and strength as a people. They know who they are, they know where they come from and how they got to where they are. They know their shortcomings and their strengths, and they know what they want and what they must do but that the ultimate power in attaining that is not theirs. This makes them a complex but noble people. For they have looked at themselves and can say, "Warts and all, this is who we are." That is a refreshing trait compared to their southern neighbors, who exhibit the baffled, reflexive confusion, followed by outrage and revenge, that characterizes almost every dominant section within a country or union. The Scots are painfully self-aware; the electors of David Cameron and Nigel Farage are aware only of others.

So now the Scots have a new paradigm in their unsatisfactory history. For more than half of their country voted to remain subservient to London. For all the blaring of "Scotland the Brave" and thumping the chest shouting "Whae's like us?" when the chips were down, Scots voted not to be Scotland but to be North Britain. They basically said, "We're proud to be Scottish, but not if it involves any pain or inconvenience."

Can you say that's Scotland? If we're using democracy as a yardstick, which we moderns are wont to do, then yes. 55% of Scots said so. And I think they expected to say to the other 45% who voted Yes, "All right, you lost. Time to roll up your saltires, go home, and get back to business as usual."

Maybe the No voters didn't want to define Scotland in such a way; maybe they resented being forced to make the choice. But they made it all the same and there are consequences for that, like every decision. They've said, "We were free to go, but we're not sure who 'we' are."

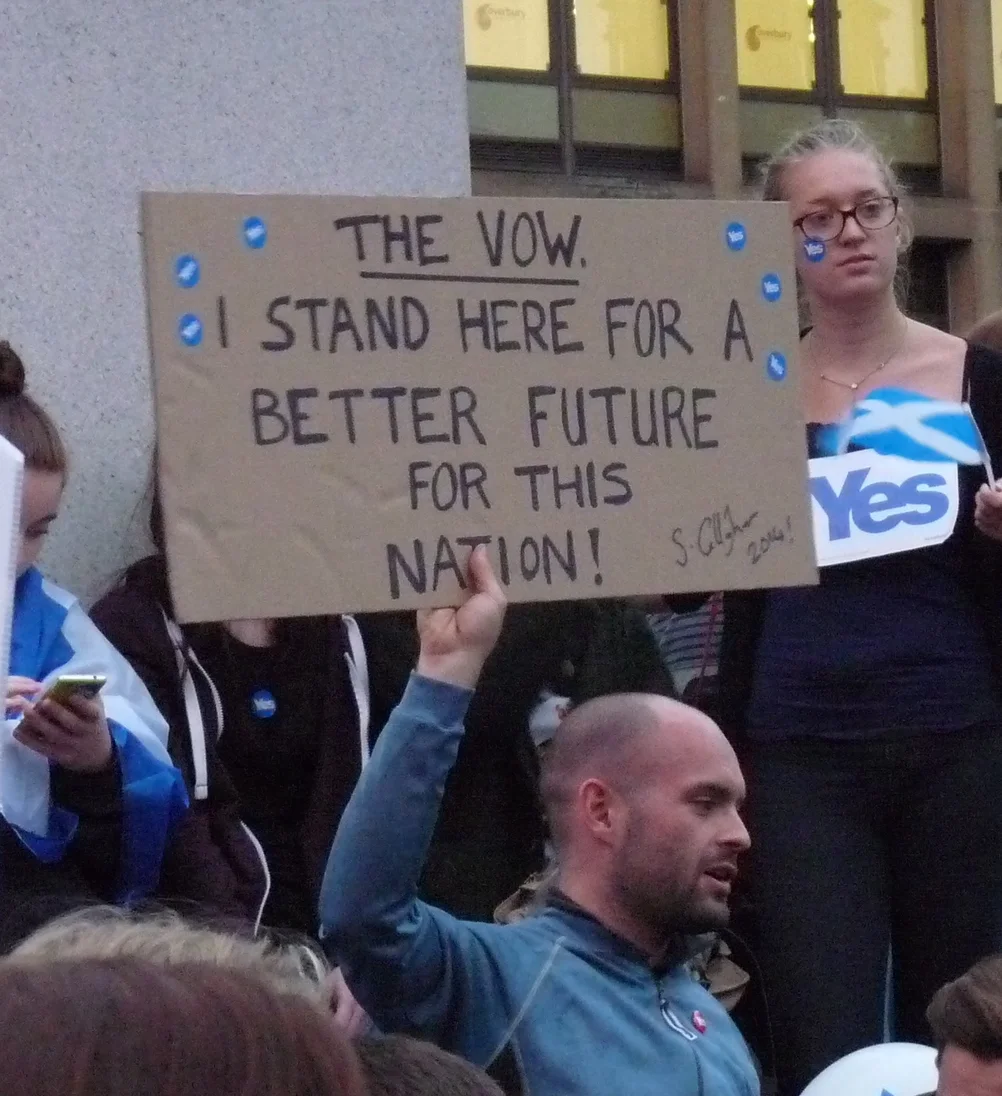

But the Yes voters were sure. They put their vote where their heart was. And they've been hurt in the heart by the result, and have responded predictably. Right now they are out joining the SNP, the Scottish Greens and Scottish Socialist Party. They are organizing rallies, gathering supplies for food banks, and thinking about the future. They are planning a new, expanded vision for their groups and platforms like Common Weal, National Collective, Radical Independence Campaign, Wings Over Scotland, or Bella Caledonia. They are looking to create new, independent media sources to present a more balanced (more Scottish?) view on current events to the Scottish public. They refuse give up and press on, still in full-on campaign mode.

Who then is taking the more active role in defining Scotland? Those who voted once and made sure, through their own loyalty, naivete, fear, or complacency the tentacles of the British state remained firmly suctioned to every part of Scottish society? That majority? Or is it the minority, who are out trying to make happen what is not within their control? If it is the former, then we have the case that there is no more Scotland. The modern world has triumphed, where the relationship that truly matters is the state and the atomized individual, where the state says, "I love you more than anything in the world, but if you ever try to leave me, I'll destroy you and everything you care for."

If it is the latter, though, then there is still a Scotland, but in a new way. It is a Scotland that is not defined by the historical borders of the country. It is a Scotland where fewer people than most believe that Scots should do things for themselves, in their own way. The Yes vote was 45% but only three out of thirty-two councils went for Yes. The Yes voters are scattered geographically across the land -- they are not concentrated in one region of Scotland, where they can separate themselves from the No-voting rest of the country if they chose. This is a great disadvantage, on the face of it, but perhaps in the long run, it is a blessing. For it keeps the angry and disenchanted from breaking away from those who see differently from them. It prevents there from being, in a geopolitical sense, two Scotlands. The case of North Korea and South Korea is an example of this: two states, where each has embraced an ideology that they believe is best for the Korean people. What they hold dearest divides them.

But there are two Scotlands at the moment. Those for whom the campaign still lives on, and those who are returning to their lives, perhaps uncaring about the result, perhaps slipping back into their old cynicism about politics after the Cameron-Miliband-Clegg "Vow" turned out to be a complete fabrication. What remains to be seen is whether there will be reconciliation or triumphalism. If there is reconciliation between Yes and No, then some sort of new iteration of Scottish identity may emerge. If there is triumphalism, then one of the two narratives will become the dominant one. And it is entirely possible, despite its minority position, that the Yes campaign will write the history. It has reason to, because it must convince future generations (even if can't convince No voters now) that it was right. But even if they are successful in that effort, what fact lurks is that the Yes campaign had to protect an idea of Scotland against the will of most Scots. It would thus be a minority view foisted on the rest by the will of the more committed.

What then is a Scotland for? Is it for what the people want, even if they don't want it as its own distinct thing, a separate and independent nation? Or is it for itself, built upon history and traditions of self-rule and those who would protect and re-articulate those traditions? How can we call for democracy on the one hand and appeal to the idea of a nation on the other when they are not used in concert? Is the fact that only a minority of Scots wanted independence an indication that, for most, countries are now merely images bought, sold, and displayed by the rulers? Is the rage of the Yes minority an indication that the nation does not actually function behind the scenes like it is purported to by every face the state presents to the public?

The fact that we must ask these questions demonstrates that we have come to a strange time in the idea of a nation. Not the nation-state, not the Westphalian creation that puts an all-encompassing centralization and homogenization at its core. Rather, it is the nation as a collection of people who have common experience; who have governed and been governed by each other; who influenced and were influenced by each other; who make something which is complex and nuanced, but not relative. It has a word -- in this case, Scotland or Scots or Scottish -- so it is real, it is a thing, distinct from others. Going into the Scottish independence referendum, I thought the moment would demonstrate the fact that people have instincts and loyalties to something older and more immediate than the abstractions of the modern state. But I can see now that I was wrong. This was no rebellion of the anti-modern. The relationship of the state, which merely uses the idea of nation or people or identity as a image to cloak itself, to the individuals it rules is the dominant one in our world. It holds the allegiance, or the fear, of most people, and makes the idea of democracy obsolete because of the codependency it fosters.

So on the one hand the state has trumped any of our attempts at recalling shared experience, memory, and community as a basis for creating (or restoring) polities that better serve the people who live in them. Yet on the other hand it is plain that large political units in the developed world are increasingly unsustainable. They centralize not only political power but also economic power and suck dry the hinterlands and the periphery. What cannot be sustained will not be; empires and mighty unions eventually crumble or disintegrate. So Scotland will have its chance again at independence, at self-rule. When it comes, Scotland may want it, or perhaps not. Whatever the case, Scotland will have to contend with its concrete and unsatisfactory history. It will have to decide what it is, why it did what it did, make peace with that, and move ahead. It will have to reconsider what Scotland is, and it will do so, I am sure. Yet the country cannot ever escape the fact that, given the clear chance after 300 years, it voted against being itself on its own terms. The Bannockburn glory, the "bought and sold for English gold" myth of Burns' lament, it all must be reconsidered in that light.

Scotland will one day be a new nation. But it will not be the same nation, just as it is not now. That is refreshing for what it can achieve and how it will make itself in its own vision. And yet it is also sad for what it leaves behind as a consequence of its own decisions, imperfect as they may be.